Nuisance & Invasive Species Found in Florida Waterbodies

Written by Christina Kennedy, Aquatic Biologist

Florida is known for its sunny beaches, palm trees, and incredible native plants and animals. However, due to its hospitable sub-tropical climate, it is not only prone to large amounts of tourists but also nuisance and invasive pests. Florida also serves as a major hub for trade, which increases its susceptibility to invasion.

One aspect of the Florida ecosystem that facilitates the spread of undesirable species is the stormwater management system. It is uncommon to find a community that doesn’t have at least one lake or pond, which is likely connected with other natural or community waterbodies. The interconnectivity of our waterways acts as a vector for invasive species to spread and become established.

Let’s take a look at some of the common nuisance and invasive animal species that could be lurking in your backyard, as well as some sustainable ways to manage or prevent them:

Island Apple Snails (Pomacea maculata)

One of the most widespread and common invasive species in Florida is the island apple snail (Pomacea maculata), native to South America. It is thought to have been introduced in the 1980s through the pet trade. One of the main differences between this species and the native apple snails is their diet. While native apple snails eat mostly periphyton (algae and detritus) their invasive counterpart feeds primarily on rooted aquatic plants. The island apple snail reproduces rapidly and established populations can pose a threat to beneficial littoral buffer plants. The most identifiable characteristic of the invasive island apple snail is the bright pink egg casings the females deposit on emergent and dry surfaces around lakes, ponds, and canals. In Florida, there are a total of four invasive apple snail species and one native species.

How can they be safely managed: The placement of screens and barriers near water inflows and outflows can help prevent this invasive species from moving to new areas. However, this method should be approached strategically to limit the subsequent threat of flooding. This method will also help congregate the existing population to help facilitate removal. Physical removal methods include removing the snails by hand or with various types of mechanical equipment. In extreme cases, a molluscicide may be applied by a licensed professional.

Cane Toads (Bufo Toads)

If you live in central or south Florida, you may have heard the slow melodic trill of the cane toad (Rhinella marina), also commonly referred to as bufo toads or bufo frogs. Cane toads are native to Central and South America and were intentionally introduced to control a pest that was threatening agricultural crops in the 1930s. In Florida, they tend to congregate and breed in freshwater around littoral plants. Cane toads compete with native frogs and toads for habitat and prey resources. They are also known for the toxin they can secrete; in fact, every stage of their lifecycle is poisonous, egg to adult. The toxin, bufotoxin, is a skin and eye irritant in humans and can be deadly to animals. It is very difficult to distinguish between the invasive cane toad and the native Southern toad. Cane toads tend to be larger than the native Southern toad, and lack the crests found on the head of the Southern toad.

How can they be safely managed: It is possible to manage cane toad populations by collecting and disposing of their eggs. Mesh fencing can also be utilized to prevent adult toads from entering protected environments. In severe cases, adult cane toads can be humanely collected and removed from the area. Because adult cane toads closely resemble native desirable species, it’s important to rely on an experienced professional for the management of these nuisance animals.

Blue Tilapia

You may have seen our next invasive pest on the shelf in the grocery store. Blue Tilapia (Oreochromis aureus) are used in aquaculture. The meat is white, flaky, and has a mild flavor. Blue Tilapia are native to North Africa and the Middle East, but they were first observed in Florida in 1961. Tilapia were introduced through several means, including experimentation as a sport fish, a forage fish, and even as a biological control for aquatic plants. It is difficult to find a lake in Florida that does not have any Blue Tilapia. Adult tilapia are a gray-blue color with a white belly and red borders on the fins. They are found in nutrient-rich lakes, ponds, canals, and even some brackish habitats. Blue Tilapia competes with native fish for prey, spawning habitat, and space. Tilapia are also cold sensitive and are often the most abundant fish observed in a cold-related fish kill. They disrupt the native food chain, impacting both native fish and plants. Chances are, if you see a tilapia in your pond it is a Blue Tilapia.

How can they be safely managed: Active approaches for removal include electrofishing, seining, and setting gill nets at optimal times to capture fish during spawning. Another technique used to control introduction is screening inlets and outlets. Screening these areas can help reduce the potential of unwanted fish from entering lakes and ponds from contaminated water sources like streams, creeks, and irrigation ditches where nuisance species can be found. However, this method should be approached strategically to limit the subsequent threat of flooding.

Armored Catfish

Our next invader hails from Central and South America. The armored catfish (Pterygoplichthys sp.) is thought to have been introduced through fish farm escapees or possibly through the aquarium trade. The armored catfish have been found in Florida dating as far back as 1951. This type of catfish is also known as a suckermouth catfish. They are bottom dwellers often found stuck to the hard surfaces where they feed on algae, detritus, and small bottom critters. They compete with native fish for prey and are found in most freshwater ecosystems, including brackish water. Armored catfish can be distinguished from native Florida catfish by the presence of the bony plating and the location of their mouth. One of the most notable issues with the armored catfish is its mating ritual. The males will burrow along canals or along the shallow pond edge to create the ideal habitat for the females to lay and guard their eggs. This burrowing habit can cause siltation—and if the population is large enough it can destabilize the bank and cause detrimental shoreline erosion.

How can they be safely managed: SOLitude Fisheries Biologists utilize strategic electrofishing, trapping, and physical removal efforts to control armored catfish. Due to the unique burrowing nature of this invasive fish, recurring management may be required to establish long-term control. Ultimately, proactive efforts are key to preventing the spread of this highly invasive species.

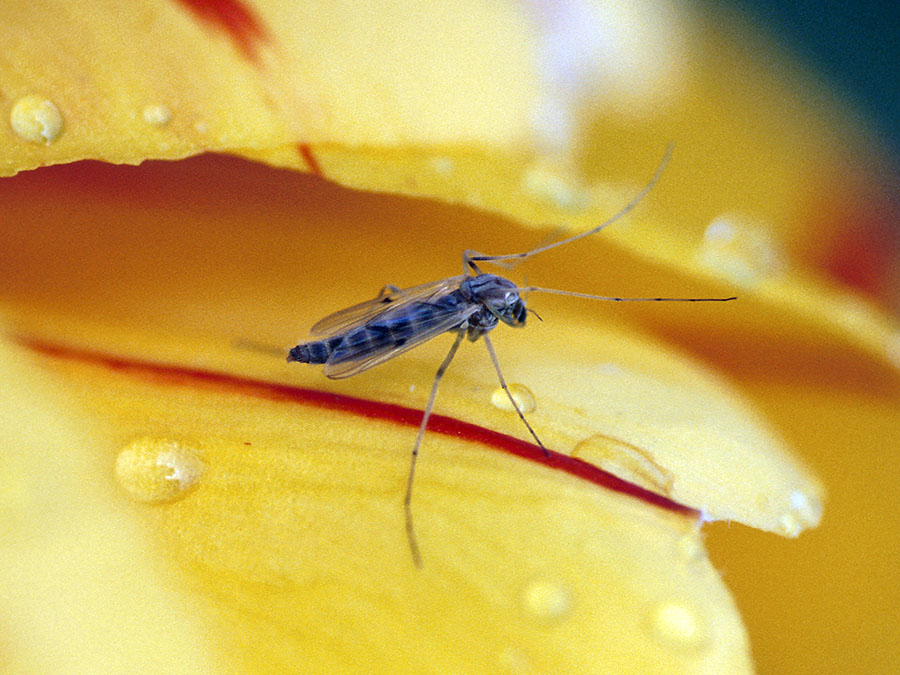

Midge Flies

Though this final pest is not actually invasive it can be quite a nuisance. Midge flies, also known as blind mosquitoes, are aquatic insects in the Chironomidae family. Adults lay the eggs in water, which then develop into larvae, then pupa, and finally emerging as adults. The adults do not live longer than a few weeks—typically long enough to reproduce. However, the adults can hatch in large swarms around ponds as they are attracted to sources of light, often accumulating on pool cages and lanais. Midges can also be stirred up in the grass or in the landscaping and are most active during dusk. Midge flies are often an indicator of water quality issues found in lakes with high nutrients, frequent algae bloom, low oxygen content, or organic muck. It is not possible to completely eliminate midge flies; however, there are options for management that can make living with midge flies bearable. The midge fly season in Florida is typically April to November. Midge fly control often requires a multifaceted approach customized to the specific property and waterbody type.

How can they be safely managed: Managing midge fly populations below nuisance levels require a multidisciplinary and proactive approach to achieve successful long-term control—starting with professional larvae count. Armed with this information, an integrated management plan can be developed to address the infestation. Depending on the unique situation, your freshwater management professional may recommend aeration or oxygen saturation treatments, strategic fish stocking, pond nutrient management, or the application of an EPA-registered insect growth regulator and/or bacterial larvicide.

Nuisance and invasive species are not inherently bad, but they can negatively impact our waterways. Therefore, the most effective management practices must begin with educational outreach and prevention. It is important to act proactively if you believe you have one of these invaders in your lake or pond. For help determining if one of these species has taken up residence on your property, contact your lake management professional who can help you design a customized management plan that seeks to re-establish balance in the freshwater habitat.